How I Finally Made Peace With My Weight—And Why It’s Not About Dieting

For years, I thought managing obesity was just about eating less and moving more. But the truth? It’s way more complicated—and deeply personal. I’ve tried quick fixes, felt the shame of setbacks, and searched for real answers. This isn’t a “miracle” story. It’s about small, science-backed changes that actually stick. If you're tired of failing diets and want sustainable health knowledge, let’s talk. Because real progress starts with understanding, not willpower.

The Myth of Willpower: Why Obesity Isn’t a Moral Failure

Obesity is often misunderstood as a failure of personal discipline. Many believe that if someone simply exercised more willpower, they could lose weight and keep it off. However, leading health organizations such as the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recognize obesity as a chronic medical condition influenced by a complex mix of biological, environmental, and behavioral factors. It is not a moral shortcoming or a sign of weak character. Framing it as such only deepens stigma and discourages individuals from seeking the support they need.

One of the most persistent myths is that people with obesity are lazy or lack motivation. In reality, many individuals with obesity are highly active, dedicated parents, professionals, and caregivers who manage multiple responsibilities daily. The assumption that inactivity causes weight gain oversimplifies a much broader picture. Scientific research shows that genetics can account for 40% to 70% of body weight variation. This means that for some people, maintaining a lower weight requires significantly more effort due to inherited metabolic tendencies.

Hormones also play a critical role in regulating appetite and fat storage. Leptin, for example, is a hormone produced by fat cells that signals fullness to the brain. In people with obesity, the body may become resistant to leptin, meaning the brain doesn’t receive the signal to stop eating—even when energy stores are sufficient. Similarly, insulin, which regulates blood sugar, can influence how the body stores fat, especially when levels remain consistently high due to frequent consumption of refined carbohydrates. These biological mechanisms operate largely outside conscious control, making the idea of “just eating less” unrealistic for many.

Environmental and psychological factors further complicate the issue. Chronic stress—common among working parents, caregivers, and those managing household demands—triggers the release of cortisol, a hormone linked to increased abdominal fat and cravings for high-calorie foods. Additionally, food environments filled with ultra-processed, affordable, and heavily marketed products make healthy choices harder, especially when time and energy are limited. A mother rushing between school drop-offs, work meetings, and dinner preparation may reach for convenient, calorie-dense meals not out of laziness, but out of necessity.

Understanding obesity as a chronic condition shifts the focus from blame to compassion and from short-term fixes to long-term care. Recognizing the biological and environmental roots of weight gain allows individuals to seek solutions that work with their bodies, not against them. This foundational mindset is essential for building sustainable health practices that support well-being over time.

What Chronic Disease Management Really Means for Weight

When we think of chronic diseases like type 2 diabetes or high blood pressure, we rarely expect an instant cure. Instead, we accept that these conditions require ongoing management, regular medical check-ins, and lifestyle adjustments. Obesity should be approached with the same level of seriousness and long-term perspective. Treating it as a temporary problem to be solved with a diet undermines its complexity and sets individuals up for repeated disappointment.

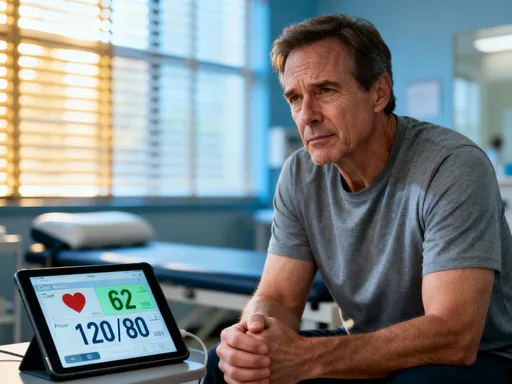

Chronic disease management emphasizes stability, monitoring, and adaptation over time. For obesity, this means focusing on consistent, measurable improvements in health rather than rapid weight loss. Key indicators such as blood pressure, blood sugar levels, cholesterol, and energy levels are often more meaningful than the number on the scale. A person may not lose significant weight but could see dramatic improvements in metabolic health through better nutrition and increased daily movement.

The concept of “health at every stage” supports this approach. It acknowledges that people can take steps toward better health regardless of their current weight. A 10- to 15-minute daily walk, choosing water over sugary drinks, or adding more vegetables to meals are all valid progress markers. These changes contribute to improved cardiovascular function, better mood regulation, and enhanced insulin sensitivity—all critical components of long-term wellness.

Effective management also involves collaboration with healthcare providers. A primary care physician, registered dietitian, or behavioral health specialist can help create a personalized plan based on medical history, lifestyle, and personal goals. Regular follow-ups allow for adjustments, celebrate progress, and address challenges before they become setbacks. Unlike fad diets that offer one-size-fits-all solutions, professional guidance ensures that interventions are safe, realistic, and tailored to individual needs.

Monitoring does not have to be burdensome. Simple tools like a food journal, a step counter, or a weekly check-in with a support group can provide valuable feedback. The goal is not perfection but awareness and consistency. Over time, these small efforts build resilience and reinforce healthy behaviors. By viewing obesity through the lens of chronic disease care, individuals can shift from cycles of restriction and relapse to a more balanced, compassionate approach to health.

The Power of Tiny Shifts: Sustainable Habits That Add Up

Many weight loss programs promote drastic changes: cutting out entire food groups, following strict meal plans, or committing to intense daily workouts. While these methods may yield short-term results, they are rarely sustainable. Behavioral science shows that extreme changes often lead to burnout, frustration, and eventual abandonment. In contrast, small, incremental adjustments—known as micro-habits—are more likely to become lasting parts of daily life.

The principle behind micro-changes is simple: consistency outweighs intensity. Instead of overhauling your entire routine overnight, focus on one manageable shift at a time. For example, drinking a glass of water before meals can help with portion control by increasing feelings of fullness. Walking for 10 minutes after dinner supports digestion and adds to daily movement without requiring a gym membership. These actions may seem minor, but when repeated regularly, they create meaningful change over time.

Habit stacking—a technique where a new behavior is linked to an existing routine—can increase success. If you already brush your teeth every night, try doing five minutes of stretching afterward. If you make coffee each morning, use that time to plan a healthy lunch. These small pairings make new habits easier to remember and integrate. Similarly, designing your environment to support healthy choices reduces reliance on willpower. Keeping fruit on the counter, placing walking shoes by the door, or using smaller plates are subtle cues that guide behavior without conscious effort.

Real-life examples show how micro-habits fit into busy schedules. A working mother might swap her afternoon soda for sparkling water with lemon, reducing hundreds of empty calories each week. A grandmother might start gardening for 15 minutes a day, combining light physical activity with enjoyment. Someone with a desk job might set a timer to stand and stretch every hour. These changes do not require extra time or money, yet they contribute to better energy, improved digestion, and gradual weight stabilization.

Research supports the effectiveness of this approach. Studies on habit formation suggest that it takes an average of 66 days for a new behavior to become automatic. The key is repetition, not speed. By focusing on what is achievable today, individuals build confidence and momentum. Over time, multiple small habits combine to create a healthier lifestyle—one that feels natural rather than forced. This method fosters long-term success because it adapts to real life, not an idealized version of it.

Food Is Not the Enemy: Rebuilding a Healthy Relationship With Eating

For many people, food carries emotional weight. It may be tied to memories of family gatherings, used as a comfort during stressful times, or associated with guilt and shame. Years of dieting often reinforce the idea that certain foods are “bad” and must be avoided, creating a cycle of restriction and overeating. The truth is, no single food causes obesity, and labeling foods as forbidden only increases their allure. A healthier approach involves rebuilding trust with food and learning to eat in a way that honors both physical and emotional needs.

Emotional eating is a normal human response. Feeling stressed, lonely, or overwhelmed can trigger cravings for familiar, comforting foods. Rather than judging this behavior, it helps to understand it with curiosity and kindness. The goal is not to eliminate emotional eating entirely but to develop alternative coping strategies and create balance. Mindful eating—paying attention to hunger and fullness cues, eating slowly, and savoring each bite—can help distinguish between physical hunger and emotional urges.

Intuitive eating principles support this shift. They encourage individuals to eat when they are truly hungry, stop when satisfied (not overly full), and give themselves permission to enjoy all foods without guilt. This does not mean eating cake at every meal, but rather removing the moral judgment from food choices. When all foods are allowed, the urgency to “eat it now before it’s gone” diminishes. Over time, this reduces bingeing and promotes more balanced eating patterns.

Nutrition also plays a vital role in supporting satiety and stable energy. Meals that include protein, fiber, and healthy fats help regulate blood sugar and keep hunger at bay. For example, a breakfast of eggs with vegetables and avocado provides lasting energy, while a sugary cereal may lead to a crash and mid-morning snack cravings. Planning balanced meals doesn’t require gourmet cooking—simple combinations like grilled chicken with roasted vegetables, oatmeal with nuts and fruit, or a bean salad with olive oil dressing are both nutritious and satisfying.

Avoiding highly restrictive diets is crucial. Programs that eliminate entire food groups or impose rigid rules often lead to nutrient deficiencies, low energy, and social isolation. They may result in short-term weight loss but rarely support long-term health. Instead, a flexible eating pattern that includes a variety of whole foods, allows for occasional treats, and adapts to personal preferences is more sustainable and enjoyable. Food should be a source of nourishment and pleasure, not fear or punishment.

Movement That Fits Your Life—Not the Gym Obsession

Physical activity is often equated with gym workouts, fitness classes, or intense cardio sessions. While these can be beneficial for some, they are not necessary—or appealing—to everyone. For many adults, especially those managing family and work responsibilities, the idea of spending an hour at the gym can feel overwhelming or unrealistic. The good news is that movement comes in many forms, and daily activity is more important than structured exercise when it comes to long-term health.

Non-exercise activity thermogenesis (NEAT) refers to the calories burned through everyday movements like walking, standing, cleaning, gardening, or playing with children. Research shows that NEAT can vary by up to 2,000 calories per day between individuals and plays a significant role in weight management. A person who walks to the store, takes the stairs, or stands while talking on the phone burns more energy over time than someone who sits all day, even if neither visits a gym.

Enjoyable activities are more likely to become regular habits. Dancing to favorite music, tending to a garden, walking the dog, or playing tag with kids all count as movement. These activities improve cardiovascular health, strengthen muscles, and boost mood without feeling like a workout. The key is to find joy in movement rather than viewing it as a chore or punishment for eating.

Low-impact options are especially valuable for those with joint concerns, chronic pain, or limited mobility. Swimming, cycling, chair yoga, and stretching routines provide gentle yet effective ways to stay active. Water-based exercises reduce stress on the joints while improving strength and endurance. Even seated movements, such as ankle circles or arm lifts, can enhance circulation and muscle tone when done consistently.

The goal is not to “burn off” calories or achieve a certain body shape, but to support overall well-being. Regular movement improves sleep, reduces stress, enhances digestion, and increases energy levels. It also strengthens the heart, lowers blood pressure, and improves insulin sensitivity. By redefining activity as a natural part of daily life—not a separate, dreaded task—individuals are more likely to stay consistent and enjoy the benefits for years to come.

Sleep, Stress, and Hormones: The Hidden Players in Weight Management

While diet and exercise are often the focus of weight management, sleep and stress play equally important roles. Poor sleep and chronic stress disrupt hormonal balance, increasing the risk of weight gain and making it harder to lose weight. Cortisol, the primary stress hormone, rises during periods of anxiety, overwork, or emotional strain. Elevated cortisol levels are linked to increased appetite, especially for sugary and fatty foods, and greater fat storage around the abdomen.

Sleep deprivation has similar effects. When adults get less than seven hours of quality sleep per night, the body produces more ghrelin (the hunger hormone) and less leptin (the fullness hormone). This imbalance leads to increased cravings and reduced satisfaction after meals. Additionally, fatigue reduces motivation for physical activity and impairs decision-making, making it harder to choose healthy foods or stick to routines.

The circadian rhythm—your body’s internal clock—also influences metabolism. Eating late at night, especially high-calorie meals, can disrupt insulin sensitivity and slow fat burning. Aligning eating patterns with natural rhythms, such as having the largest meal earlier in the day and finishing dinner several hours before bed, supports better metabolic health. Similarly, exposure to natural light during the day and minimizing blue light from screens at night helps regulate sleep-wake cycles.

Practical strategies can improve both sleep and stress management. Establishing a consistent bedtime routine—such as reading, taking a warm bath, or practicing deep breathing—signals the body that it’s time to wind down. Creating a screen-free zone one hour before bed reduces mental stimulation and promotes relaxation. Setting boundaries around work, social obligations, and digital use can also reduce daily stress. Simple techniques like five-minute breathing exercises, journaling, or spending time in nature help reset the nervous system and lower cortisol levels.

Rest is not laziness—it is a foundational pillar of health. Prioritizing sleep and stress reduction supports hormonal balance, improves mood, and enhances the body’s ability to manage weight naturally. When these elements are in place, other healthy habits become easier to maintain. A well-rested, calmer mind is more capable of making thoughtful choices and staying consistent with long-term goals.

Putting It All Together: A Realistic, Science-Backed Approach You Can Live With

Sustainable health is not about following a rigid set of rules or achieving a specific appearance. It is about creating a flexible, personalized framework that supports long-term well-being. The key elements—nourish, move, rest, and support—work together to build resilience and promote lasting change. Nourish means eating balanced, satisfying meals without fear or restriction. Move involves finding enjoyable ways to stay active throughout the day. Rest includes prioritizing sleep and managing stress. Support means seeking guidance from healthcare providers and connecting with others on similar journeys.

Progress is rarely linear. There will be days when old habits resurface, schedules become overwhelming, or motivation dips. This is normal. Self-compassion is essential—treating yourself with the same kindness you would offer a friend facing a challenge. Instead of aiming for perfection, focus on consistency and effort. Celebrate small wins, like choosing a healthy snack, taking a walk, or getting to bed on time. Each positive choice reinforces the habit and builds momentum.

It’s important to remember that health is not defined by a number on the scale. Improved energy, better sleep, reduced joint pain, or feeling more confident in daily activities are all meaningful signs of progress. These changes often occur before significant weight loss and are strong indicators of improved metabolic health. By shifting the focus from weight to well-being, individuals can build a more positive, sustainable relationship with their bodies.

Before making major lifestyle changes, consulting a healthcare provider is strongly recommended. They can assess individual health status, identify any underlying conditions, and offer tailored advice. This is especially important for those with chronic diseases, mobility limitations, or medication concerns. Professional support increases safety and effectiveness, ensuring that changes are appropriate and beneficial.

Managing obesity isn’t about perfection—it’s about persistence, understanding, and self-respect. By shifting from quick fixes to lifelong health knowledge, we build resilience. Small choices, made consistently, create real change. And while the journey is personal, no one has to walk it alone.